How Picasso and Giacometti Inspired a New Exhibition in the Middle East

Previously published in The National.

In 1932, at the age of 52, Pablo Picasso had his first museum exhibition. It was at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, and it contained 460 pieces of art – mostly paintings and drawings.

It is, perhaps, telling of Picasso’s character that he was his own curator for this seminal show. Even during his own lifetime, he was filled with enormous self-confidence and made great efforts to promote his extraordinary talents.

He was almost the polar opposite of Alberto Giacometti, a serious, shy Swiss artist 20 years his junior, who spent most of his days working in a tiny Paris studio with a very limited social life. Yet Giacometti greatly admired Picasso – it’s documented in his notebooks that he visited this exhibition in Zurich several times, made sketches and tried to reproduce Picasso’s paintings.

By this time, the pair had already struck up an unlikely friendship. Giacometti wrote in his diary about regular visits to Picasso’s studio and welcoming the older artist to his. He also recorded conversations the pair had during lunches or dinners in the cafes around Montparnasse, the district at the heart of intellectual and artistic life in Paris in the 1930s.

This information only recently came to light when two French institutions joined forces for a two-year research project. The Fondation Giacometti and Musée National Picasso cross-referenced their archives and conducted interviews with living relatives, including Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s partner during this period.

Once the depth of the relationship became clear, Catherine Grenier, the director of the Fondation Giacometti, along with two associate curators, Serena Bucalo-Mussely and Virginie Perdrisot, put together an exhibition of 120 pieces by the two artists to illustrate the impact that their friendship had on their careers, as well as their obvious differences.

Picasso-Giacometti ran from October to February at the Musée National Picasso in Paris, then travelled to Qatar, where it’s currently at the Fire Station Artist in Residence Centre in Doha, after opening last month. It’s the first time many of these works have been shown in the Middle East.

This exhibition is also is the first time these two artists have been compared in a scholarly fashion, which is important, not least because Picasso was a notoriously difficult character. His friendship with Giacometti seems to reveal a lot of respect for the younger’s talents.

"Picasso was not always very friendly with other artists," explains Christian Alandete, head of exhibitions and editions at the Fondation Giacometti. "He was very self-confident and knew that he was an excellent painter. He would not entertain other artists whom he didn’t consider to be on the same level. From our research, we can assume that Giacometti was the only artist that Picasso saw as an equal and that is why they became good friends."

Grenier, the exhibition’s principle curator, elaborates: "Although there was a 20-year age difference, they found themselves as equal artists following similar experiences that led to very different responses, but always with a strong visual impact. Furthermore, they sometimes created a dialogue with their own artworks by working on the same motifs."

This is made clear at several points throughout the exhibition, where specific works are used to show their shared influences and techniques.

Early sculptures by both artists are modelled on the art of Auguste Rodin, but as their careers progressed, Picasso’s influence on Giacometti can be seen, particularly in a sculpture of his sister Ottilia that he made in 1925. In it, he abandoned the classical technique and instead adopted the stylised lines and multifaceted cubist planes used by Picasso in the 1906 and 1909 portrait sculptures of his companion Fernande Olivier.

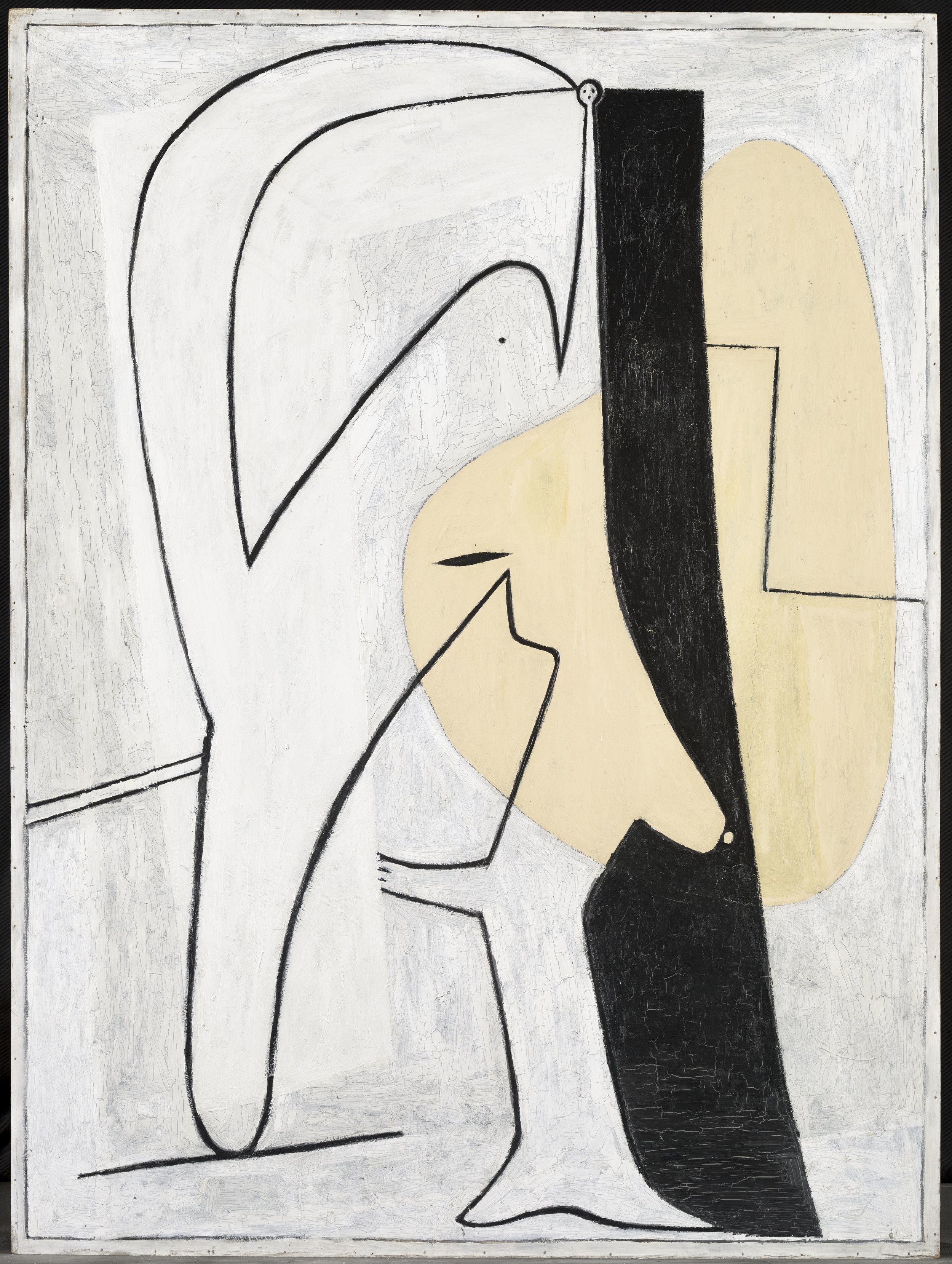

Picasso’s paintings from the neo-cubist period of the late 1920s were characterised by a shift to the flat plane, which Giacometti applied to sculpture.

The exhibition displays a 1927 painting of Picasso’s called Figure next to a 1928 sculpture by Giacometti called Woman (Flat III), an abstract and almost two-dimensional figurative head.

In the 1930s, both artists followed the movement of the Surrealists, with Giacometti briefly joining the group. During this time, both artists created dreamlike images and distorted figures clearly seen in Picasso’s painting Woman Throwing a Stone, where the lines and forms are echoed in Giacometti’s sculpture Disagreeable Object. Both were completed in 1931.

Although they had wildly different personal lives, Picasso and Giacometti both created many portraits of the women they loved. While Picasso had many wives and mistresses, who usually became his muses, Giacometti was a one-woman man. The exhibition compares an image of Dora Maar, Picasso’s principal model from 1935 to 1943, with a sculpture (pictured on the cover) of Annette Arm, whom Giacometti married in 1949.

After the Second World War, both artists shifted towards representation of everyday life and reality, including human figures, landscapes and animals.

Giacometti’s famous 1951 bronze sculpture The Dog is actually the slender silhouette of the Afghan hound that belonged to Picasso, and in the exhibition, it’s directly compared to Picasso’s 1950 sculpture The Goat, also made from bronze.

However, during this year, the friendship came to an abrupt halt. Picasso opposed Giacometti’s entry into Louise Leiris’s gallery in Paris, a leading gallery in the city, and the two men fell out based on this disloyalty. Giacometti was also increasingly disapproving of Picasso’s unabashed star status, and the tension between them escalated to breaking point.

It didn’t affect their careers. Giacometti signed up to the Maeght Gallery in Paris, and they held a solo exhibition for him that same year.

The exhibition contains paintings, sculptures, sketches, photographs and interviews with the artists that highlight the timeline of their friendship and place their art in dialogue with each other. In doing so, it opens a window into an entire period of history that is rarely exhibited in this part of the world.

To aid understanding and appreciation of Middle East audiences, the curators worked with Qatar Museums on an educational programme, including lectures, guidebooks and discussion panels. Importantly, they also worked with local teachers to educate them not only on Picasso and Giacometti’s art, but also on the modern period in Europe.

"We were aware this exhibition might be the first encounter with western Europe modernity for most of the local audience, and we decided, with Qatar Museums, to build an intensive educational programme prior to the opening," Grenier says.

This introduction to the history of art was attended by more than 200 people and was extended to the opening days with an extra session inside the exhibition.

"Our main goal over the past few years has been to bring Giacometti’s works to countries he had never been exhibited before," Grenier concludes. "We were very interested to come to Doha, particularly to this location in a building that has been recently renovated, and that we helped to adjust to international museum standards. It’s always a pleasure to see an audience react to his works."

Picasso-Giacometti ran from February 22 until May 22, 2017 at the Fire Station Artist in Residence Centre in Doha. For more information about the exhibition, visit www.qm.org.qa