Mahmoud Khaled's proposal for an unprejudiced world

The day after Mahmoud Khaled left Istanbul following the unveiling of his new commission at the 2017 biennial, he saw the news that police in Cairo had arrested seven concert-goers for raising a rainbow flag during a performance by Lebanese rock band Mashrou’ Leila.

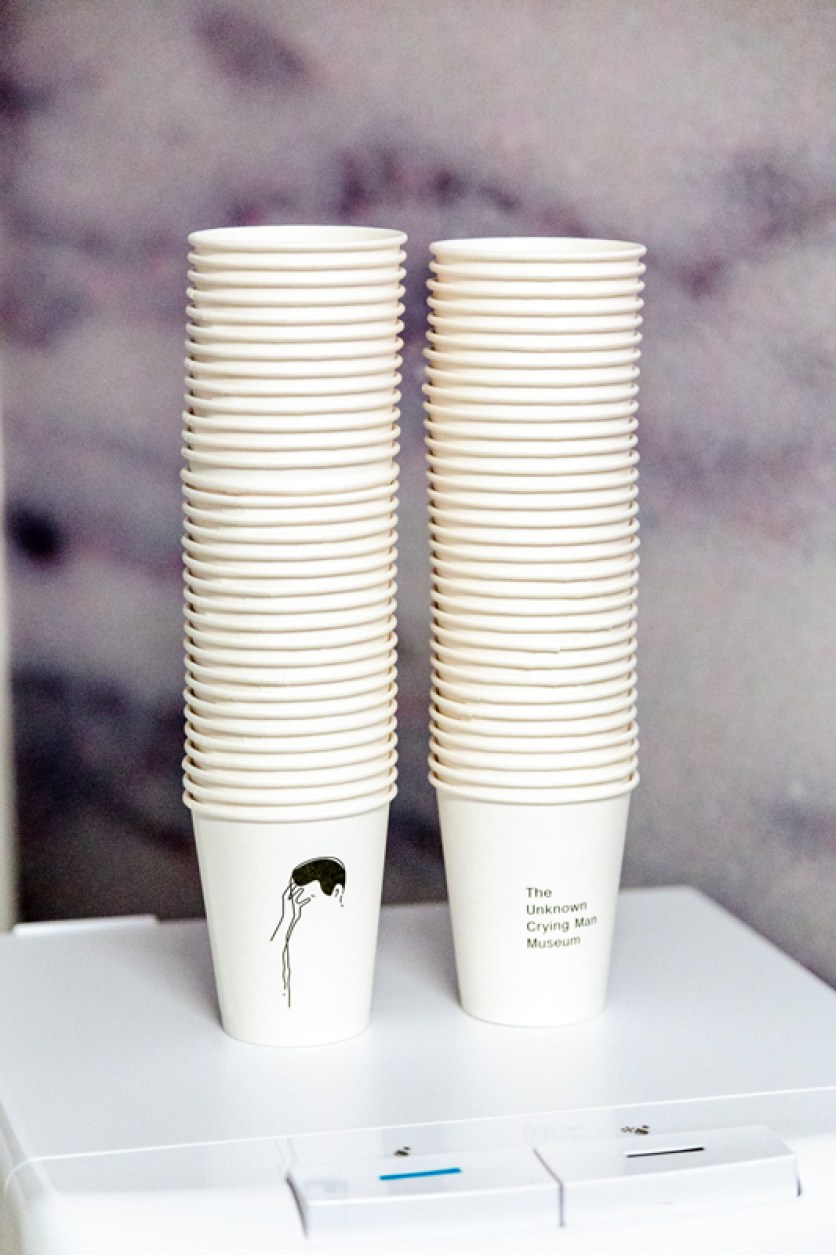

Khaled, an Egyptian who lives and works in Norway, addresses topics of gender and sexuality in his practice and the Istanbul Biennial commission tackled the issues head on. For Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017), Khaled transformed Ark Kültür, an art centre in a 1930s’ residential property, into the elaborately fictionalised home of a protagonist who has fled Cairo to live in exile in Istanbul. As his starting point, Khaled took the trial of 52 men who were arrested in 2001 aboard a floating gay nightclub in Cairo. During this highly publicised ordeal, one of the men was photographed crying and covering his face with a white cloth. Until today, that image remains a symbol for the homosexual community in Egypt, whilst the man’s identity and humanity have been sidelined.

Khaled’s installation delved deeply into this symbolic usurpation of individuality and evoked great sympathy for what that crying man represented: a personification of the LGBTQI community, not just in Egypt, but in Turkey and across the rest of the world.

Through a tightly curated audio guide, visitors to Khaled’s installation found themselves moved from room to room with their gaze directed at the poignant details of the crying man’s life, which conveyed a profound sense of melancholy, but in a poetic and elegant way.

His shelves were full of un-inscribed trophies longing for accomplishments yet to come and, in his shower, a monitor continuously played a seven-minute scene from Maher Sabry’s movie Toul Omry / All My Life (2008) – the first Egyptian film to openly address homosexuality, including the case of the Cairo 52. The table was laid with a single place setting, while upon the crockery, and in several other places around the house, a replicated image of The Crying Boy, a mass-produced print of a painting by Italian painter Giovanni Bragolin, could be found. Part of his own childhood, Khaled remembers this kitsch image hanging in the family home and in those of most of his friends. Just as nobody could ever tell him why the boy was crying or indeed, who he was, when Khaled realised that the image of the man under arrest covering his own tears was also becoming commodified, he was moved to try to construct a world in which a person’s actions in private were not a matter for public scrutiny.

This is, of course, as idealised as the proposed house museum itself, which suggests that the legacy of someone as faceless and as publically shunned as the original crying man would be given weight.

What must be celebrated about this installation is the provocation to viewers to reconsider their own judgement, question patriarchal systems and, also, reflect on the fact that deep seated prejudices continue to fester, even within societies championing notions of progress.

- A version of this article appeared in print in Selections, Letters From The Past #43 pages 62-63.