The Facilitator

BY ANNA SEAMAN

The word “fikra” is usually translated from Arabic to English as “idea” or “thought” but it also has loftier meanings: “concept”, “notion” or even “visualisation”. For Salem Al-Qassimi the word itself was an inspiration. In 2006, he founded Fikra, an experimental design studio in Sharjah, to address the bilingual nature of the UAE and to create visually appealing and culturally appropriate messaging that reflected Arabic as well as Western cultures.

“Our concept was to create honest narratives that illustrate the somewhat unique fusion of identities in the Gulf and the UAE,” Al-Qassimi says. He was frustrated that in branding and communication Arabic was becoming secondary. Fikra was the first graphic design studio in the UAE to give Arabic typography equal status with English. “My aspirations were to exhaust design as a tool or a method for communication about our culture and see how design can change that narrative.”

Al-Qassimi did not want to place any limits on the work. In the beginning, the Fikra team designed T-shirts, posters, furniture and games. They took on typographic and branding contracts. Al-Qassimi enlisted calligrapher Wissam Shawkat to create typefaces that could respond to the concept of the publication or brand, and created messaging that reflected Arabic as well as English. Clients typically straddled both cultures, such as the exhibition and studio space Tashkeel or the Dubai fashion house Bouguessa and, more recently, New York University Abu Dhabi.

“When Fikra first started there were no design studios in this part of the world—only branding or advertising agencies—so I wanted to ensure that I was creating a place for enquiry and play. We needed space to evolve,” Al-Qassimi says.

Although Fikra accepted diverse projects, Al-Qassimi refused to compromise on principles, even after the 2008 financial crash. “We had to take risks and I had to make decisions to turn away clients who were asking us to do things that we just didn’t believe in,” he explains, mentioning being asked to use Photoshop to manipulate images for modesty by adding sleeves or other clothing parts. “We gave it six months, and that is when we had to become as creative as possible. We were a small studio and we managed to weather the storm.”

The following year, Al-Qassimi began a two-year master’s in graphic design at the Rhode Island School of Design in the US. The perspective on his home country compelled him to further investigate the UAE’s hybrid identity. His thesis, titled “Arabish”, was a study of the country’s bilingual culture.

While Fikra worked to fill a void, Arabic graphic design education was almost non-existent. In 2012, Al-Qassimi began teaching Arabic-language typography and design at the American University of Sharjah.

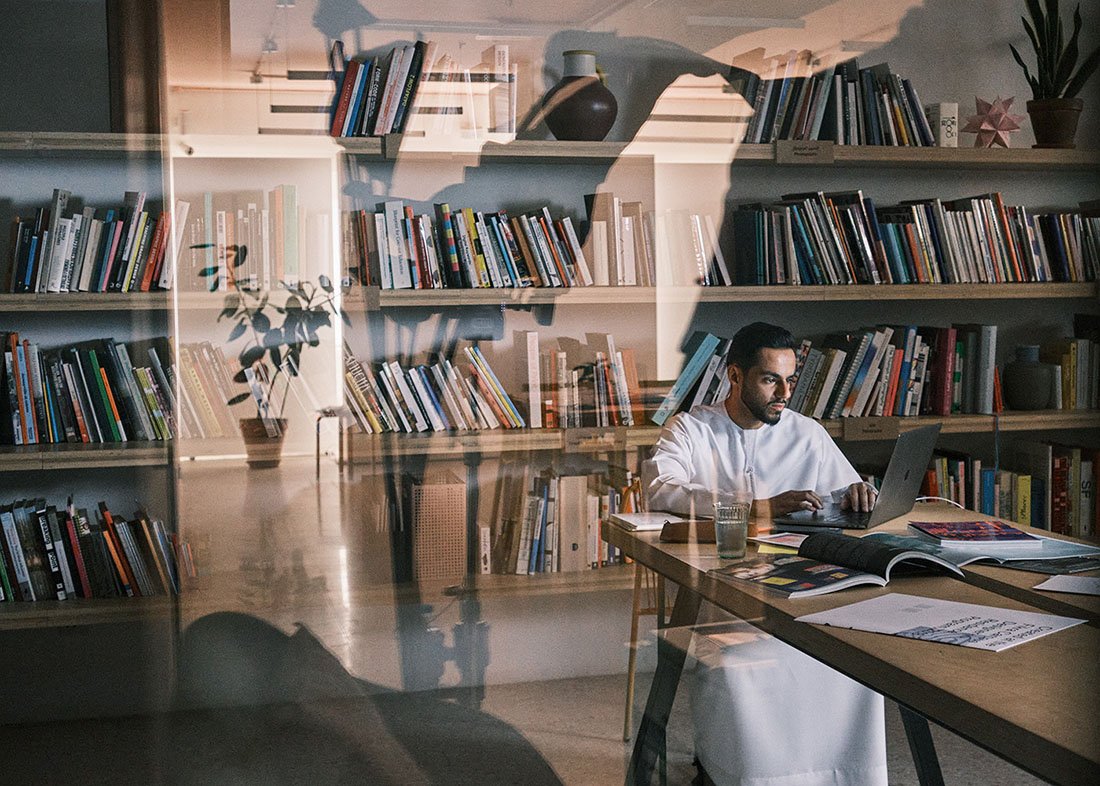

He and his wife, Maryam Al Qassimi, who joined Fikra in 2013, have expanded the venture, launching Fikra Campus in a building on the border between Sharjah and Dubai which encompasses Fikra Design Studio, a cafe, gallery, co-working space, and library. It hosts programmes year-round, such as workshops, talks and film screenings.

“It is not just a co-working space; it is a space you can work from and learn from,” Al-Qassimi explains. “The business model is also loosely not for profit—the income that comes in mostly goes back into the spending for the campus. This is because I am always thinking about social responsibility and the importance of knowledge building.”

The Fikra Designer-in-Residence programme is a three-month stint that culminates in an exhibition. Forming Outlines, the product of the 2019 designers—Mashael Alshammary and Sara Khalid from Saudi Arabia and Layan Attari and Moylin Yuan, based in the UAE—was scheduled by Fikra and partner Misk Art Institute for a physical exhibition in March in Riyadh. However, due to the pandemic, the display shifted to a digital show, which suited the breadth of the work as it emphasised that the research presented is inconclusive and evolving.

Al-Qassimi’s lively “Fikra Talks” series has included a discussion with German graphic designer and publisher Lars Harmsen and photographer, journalist and lecturer Dirk Gebhardt about how one might explain mankind to man with images. “The Cultural Salon”, a discussion and debate series he runs jointly with Sharjah’s 1971 Design Space, seeks to engage the local community in topics relevant to the UAE. In its third edition it explored the importance of pearls to the country, from pearl diving to their use in contemporary design.

Perhaps the most far-reaching initiative is the Fikra Graphic Design Biennial, which launched in 2018 to critical acclaim. For the inaugural presentation, Fikra transformed a derelict bank in Sharjah’s Bank Street into the fictional Ministry of Graphic Design, with “offices” organised by themes that exhibited works from practitioners from 33 countries looking at how design can be used to change social narrative.

Plans for the 2020 event are underway and will reflect upon the pandemic that has dominated life globally this year. “We will question what does the biennial mean in this digital world as well as what would it mean if it didn’t exist in the traditional format,” Al-Qassimi says. “We are also looking at how we engage people by only using the internet and social media if we can’t host anything on a physical platform.”

His creativity was encapsulated in an artwork that Al-Qassimi created for an exhibition in Sharjah’s Maraya Art Centre in 2014. The work, titled Bilingual Scripting, used computer technology to create an interactive form of a new alphabet fusing Arabic and Latin letters and sounds together. However, the team at Fikra are constantly adapting current design challenges to the unique DNA of the UAE. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the studio hosted an online series called “Conditions”, which addressed mid-pandemic situations through a series of online events—talks, workshops, film screenings, and readings.

Fikra Campus encompasses Fikra Design Studio, a cafe, gallery, co-working space, and library. While he has accepted diverse design projects, Al-Qassimi has been careful to ensure that he is creating a place for enquiry and play, a space to evolve.

“Research is a big part of what we do now,” Al-Qassimi says. “We conduct design-thinking inter- views, create prototypes, develop research methodologies and collect data to make plans and reports all through the lens of design.”

The flexibility of Al-Qassimi’s outlook and organically allowing the studio to adapt and change is what laid the groundwork for Fikra to become what it is today. Recent clients include the Early Childhood Authority in Abu Dhabi, which is part of the Sheikha Salama Foundation; the Institute at New York University Abu Dhabi; and spearheading the visual campaign for events such as Sharjah International Book Fair and the 2017 edition of Art Dubai.

“Right now, we are in a good place,” he says. “People come to us for a very specific way of thinking and the type of work that we deliver. However, the work we do in the community is also extremely important.”

Al-Qassimi is an accomplished writer and an engaging speaker. In February, he spoke at the Future Design and Design Future conference in Cairo. “I was thinking about my role in the traditional sense of design and about the vast possibilities of what a designer can do,” he says of his talk. “Reflecting upon that I realised that much of my work over the past few years has been a facilitator of conversations, entrepreneurship, thinking and cultural dialogue.”

While Al-Qassimi actively creates initiatives, he also attributes his success to the lucky connections they bring.

“You must never underestimate serendipity in the way that things happen. When we designed Fikra Campus and when we think about our programmes and platforms we do so with serendipitous encounters in mind,” he says. “Maybe you can say we are facilitating serendipity.”