Wolf Tone: a group exhibition

This is a curatorial essay written for the opening of Wolf Tone, a group exhibition I curated with XVA Gallery in Dubai. The opening was on Jan 13, 2020.

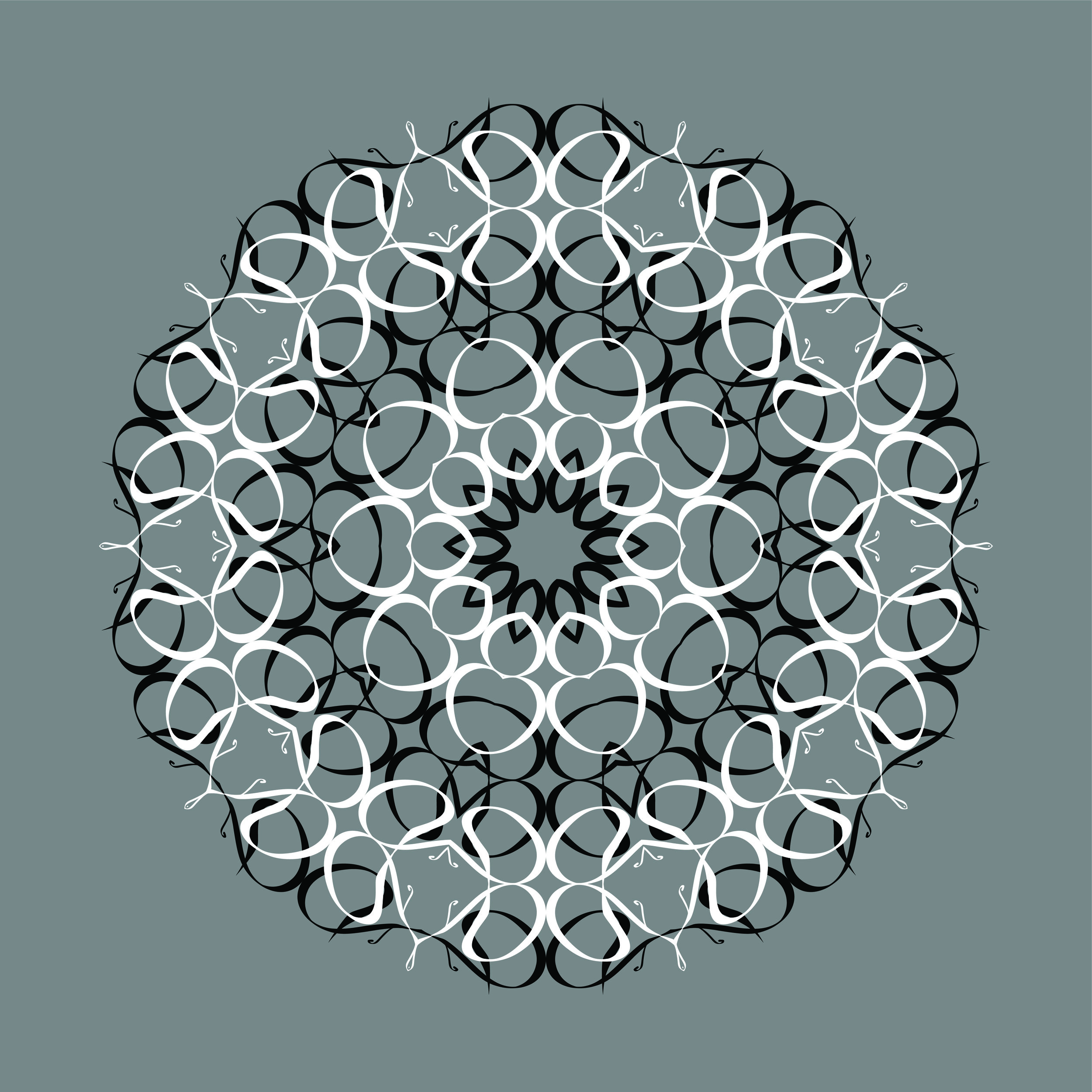

Daniah Al Saleh, Disobedient Affects (2019). Image courtesy of the artist and XVA Gallery.

WOLF TONE: Circles of Life

In Platonian thought, the perfect circle exists only in the realm of ideas, remaining purely theoretical. Its seamless form and changeless format are merely reflections of a dimension beyond our physical reach. It is a representation of the infinite, revealing the ultimate unknowability of nature.

The five canvas panels that comprise Daniah Al Saleh’s Disobedient Affects (2019) are filled with grids of circles in various shades of white. The shapes seem to be flawless, painted to mathematical precision, however the artist has made deliberate imperfections along the edges. Within the boundaries of each canvas, she has placed a seven-inch monitor upon which a similar, yet much more precise, digital circle moves according to a computational formula that Al Saleh has devised. The contrast between the hand-painted and digitally-made circles creates a space of tension. Does the viewer ask for unity and conformity thus seeing the animated circle in a disobedient act of rebellion, or does the movement of the pixels represent freedom against the grid-like restraints surrounding it?

Inspired by a psychological study of human behaviour – An Experimental Study of Apparent Behaviour by Fritz Heider & Marianne Simmel (1944) – there are anthropomorphic questions at play here. These circles are almost identical yet also unique. They are geometric constructions; yet their conformist grids are microcosms for society and the expected social norms that communities rely on in order to function. The digital circle therefore, encapsulates the complexity of the piece. Emancipated from the rigidity of the static and perceived perfectionism of its surroundings, the digital circle is free to express itself. But to what extent is it really free? The social norms expected of any individual in a liberated society are almost always tied to the constraints of the world it functions in. The circle, no matter how much it rebels or protests against the controlled environment, is still a circle, maintaining its form in order to maintain its identity. However, each one functions under a computational glitch, giving rise to a subtle movement that the viewer associates with some kind of human emotion, the meaning of which is subjective. As with the Heider & Simmel study on interpersonal perception within which simple shapes are assigned emotional characteristics based on their movements, human emotional behaviour pivots around unspoken interpretations of minimal gestures and facial expressions.

Amal Al Gurg, Haram/Halal (2019). Image courtesy of the artist and XVA Gallery.

Here, the movement of one rogue circle in an otherwise structured grid offers speculation upon the impossibility of reaching perfection, whether mathematical or behavioural. The perfect circle and likewise the perfect human, does not exist. Furthermore, its glitched and thus unpredictable movements offer a source of agitation, which the human eye instinctually wants to remove. Much like the unwanted wolf tone.

A wolf tone in musical terminology is a name given to an artificial overtone that amplifies and expands the frequencies of a played musical note and is produced when the original note matches the natural resonant frequency of the body of the stringed instrument it is played on. Most musicians try to eliminate these wolf tones, which are considered problem notes.

Wolf Tone the exhibition uses the term metaphorically, shedding light on the minutiae of life that we overlook or explaining them in a way that allows the audience to take notice of the previously ignored.

Huma Shoaib, To Fly Towards a Secret Sky (2019). Image courtesy of the artist and XVA Gallery.

Al Saleh’s disruption of the circle as an embodiment of perfection is somewhat echoed in the sacred geometry of Huma Shoaib’s paper-cut layered drawings couched between acrylic sheets. The honey bee protagonists are confrontational and defensive in their stance and upon close inspection, the insects are slightly displaced from the perfect formulae upon which their compositions are based. An existential metaphor as well as loaded with ecological and spiritual significance, the circular positioning of the bees is significant, mirroring the circulation of pilgrims around the Kaaba or the whirling motion of a dervish. With titles borrowed from Rumi’s poetry, these works come together as individual building blocks to create rhythmic wholes.

The components of language play a leading role in the work of Amal Al Gurg who relies on calligraphy as a tool in her graphic practice. Her silkscreen print Haram/Halal uses iterations of the Arabic letter ha (ح) in black and white on a grey background. The first letter of both Arabic words haram and halal, loosely translating to ‘forbidden’ and ‘allowed’, Al Gurg has cleverly used a fusion of concept and design to pinpoint the grey area between boundary points of the Islamic faith and, indeed, between so many other societal constructs that may seem to lie at extreme ends of a scale that is often blurred or at least, sliding.

Such multiple layers of lived experience surface at intervals in this exhibition. The large paper collage pieces from Elizabeth Dorazio’s series titled On Nature create an illusion not of reality but of imagined landscapes. These textured paper drawings in pastel tones are layered upon each other to give depth and dimensionality as well as speaking of the layered nature of our complex universe. Inspired by Greek philosophers who derived scientific theory, as well as societal law from the order and structure they found in the natural world, Dorazio works as a geologist as well as an anatomist uncovering universal secrets and providing a space for reflection.

Arezu. Untitled 01 (2019) Life Goes On from the series That Obscure Object; 25x35.5cm collage on paper. Image courtesy of the artist and XVA.

In That Obscure Object: Life Goes On, Arezu uses mixed media collage to explore the female condition as marginalised. Her work is simultaneously personal, revealing concerns about censorship as well as patriarchal control and worldly, offering almost experiential compositions. Her use of the body in her work is deliberately provocative, redefining the meaning of objectification and questioning the meaning of subject, or agency.

With her delicate practice, Naz Shahrokh takes a tactile approach and subtle processes often give new meaning to her materials. The series comprises photographic works that depict roads or landscapes upon which the artist has written the phrase ‘j’arrive’ in a repetitive manner. This phrase has no direct translation from French but could mean either ‘I arrived’ or ‘I am on my way’; the repetition both enforces and reduces the meaning of the phrase; conceptually, it acts as a device to focus the viewer on the journey of life itself.

Naz Shahrokh, J’arrive (E from a series of 7). Image courtesy of the artist and XVA Gallery.

Also present here is the question of what it means to eliminate life’s nuisances or wolf tones. At the risk of sounding cliché, it is the hiccups along the way that often make the journey worthwhile and, sometimes, the destination unimportant.

An artistic interpretation of the exhibition’s title led Stephanie Neville to consider the things we take for granted in all aspects of life. Her colourful, tangible approach unites here in pieces from three separate series focusing on the small gestures, casual words and throw-away comments that are the binding glue in loving relationships. The white-on-white pieces point to the subtlety of her artistic observations and the soft sculptural floor pieces pay reference to the cosy yet often commercialized aspects of love in the contemporary sphere.

The cornerstones of this show are not immediately obvious. That which appears from the outside to be inconsequential, often reveals itself to be crucial. Much as with the case of the circle, what we are actually seeing is not the perfect shape but an approximation of such with so many nuances hidden in the proverbial grey area. Perhaps, if this exhibition could be summarized in a single image it would be of a grey circle, which is neither perfect nor clear-cut but a representation of lived experience.

Stephanie Neville, Mine (2019) from the Blushing Bride series. Image courtesy of the artist and XVA Gallery

Wolf Tone. January 11 - February 18, 2020. XVA Gallery, Dubai.